- Home

- Martina Scholtens

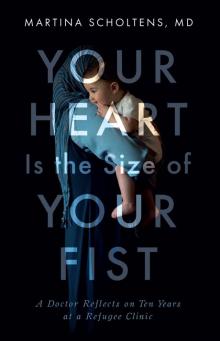

Your Heart is the Size of Your Fist

Your Heart is the Size of Your Fist Read online

For Pete

CONTENTS

Preface

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Notes

About the Author

PREFACE

I WORKED AS A FAMILY DOCTOR at Bridge Refugee Clinic in Vancouver, Canada, from 2005 to 2015. The clinic provides care to one to two thousand new refugees arriving in British Columbia each year. I started fresh out of residency, spent my thirties there, and ended up becoming the clinic’s medical coordinator. As a clinical instructor with the Faculty of Medicine at the University of British Columbia, I supervised a steady stream of students and residents over the years. I heard and told a lot of stories.

My clinic days end with charting—updating the patients’ medical records with their concerns, my findings, and our plan. But I often follow that with writing down for myself the details of something that moved me that day. Sometimes I write to reflect, sometimes to memorialize the patient.

There is a third reason I write: advocacy. I support refugees, the Canadians who welcome them, and a robust refugee policy. With increasing media coverage of refugees following cuts to federal health coverage in 2012, Canada’s commitment to Syrian refugees in 2015, and policy changes south of the border in 2017, I read and listened to a myriad of opinions on our country’s newest residents. Much of what I encountered was inconsistent with what I saw in my exam room. I thought my vantage point might be worth sharing.

This book was written with the utmost respect for patient privacy, for what the Hippocratic Oath calls “holy secrets.” While all events and conversations depicted in this book occurred in some form during my decade at the clinic, details have been altered so that the patient cannot be identified. Some stories are a composite of multiple patient encounters, about an experience common to many refugees. Others stories are shared with patient permission; even then, I have not used their names. I have made every effort in the details included, withheld, and modified to preserve the trust of both the doctor-patient and the writer-reader relationship.

1

EAGER TO PRACTISE HIS ENGLISH, Yusef waived my offer of an Arabic interpreter for his appointment with me, as he usually did. After a year in Surrey, a suburb of Vancouver, Canada, he and his wife, Junah, had mastered the language enough to order lamb from Save On Meats and to ask the bus driver for directions to the refugee clinic at Main and Broadway in Vancouver. They did not, in fact, have the fluency for a doctor visit.

I ushered the couple into my exam room, where they sat down, beaming.

Yusef came straight to the point: “I want to kill you.”

“Pardon me?”

“I want to kill you.” He gazed straight at me. I stared back, wondering if I’d need to use the panic button hidden beneath my desk. He was composed and spoke quietly; it was hard to know whether to take this as reassuring or chilling.

“I try, this week,” he went on. “Twice, I try to kill you.” His wife nodded.

I thought back over my week. It had been uneventful. “Tell me more.”

He pointed to the phone. “I try to kill you. But no one answer.”

“Oh! Call me! You tried to call me!”

“Yes, yes, call,” he corrected himself. “What mean kill?”

“Murder. Make me dead.”

They laughed until they had to dab at their eyes with tissues.

I laughed too, a chuckle of relief. I marvelled that they were crying with laughter at a joke about death. A year ago, I’d never have believed it.

“YUSEF HADDAD?” I CALLED INTO the waiting room after consulting my day sheet. “Junah Haddad?”

The clinic waiting room was furnished with salvaged church pews, the oak worn smooth from years of waiting on God and the doctor. The furniture had struck me as incongruous when I started at the clinic, but I’d since decided it wasn’t that unnatural a fit. Church and clinic were both places where people gathered to seek answers, sites of congregation and confession.

A family of four sat patiently on the pew at the far end of the waiting room, facing me, beneath a window overlooking the parking lot. They didn’t seem bothered that the clinic was running fifteen minutes late. They looked resigned, like they were accustomed to waiting. They fit the demographic of the new family scheduled to see me that afternoon: an Arabic couple in their forties, with two teenage children. They stood uncertainly as I repeated their names. They looked tired and bewildered.

They’d arrived in Canada earlier in the week and were staying at Welcome House, transitional housing in downtown Vancouver, until they found permanent housing. I knew their past few days would have been a confusing rush of orientation sessions and registration for everything from a bank account to health insurance. The husband held a transparent sleeve containing the paperwork the family had been issued in the past week.

I extended my hand and introduced myself. “I’m Dr. Scholtens.” Sometimes Muslim men refused my offered hand, believing that Islam forbids non-essential contact with a woman who is not wife or family. Yusef didn’t hesitate to grasp it. He didn’t smile, but his eyes met mine. He was tall, over six feet, with wide shoulders and a narrow waist. He was well-groomed, hair slicked back, dark moustache neatly trimmed. He wore a button-down shirt and navy trousers. His shoes gleamed with fresh polish.

Junah’s handshake was quick and tentative. A white headscarf with a green print band was wrapped tightly around her face, without a wisp of hair showing. She was almost certainly a brunette, but with her blue eyes and fair skin, I could imagine her as a blonde.

The teenage son was almost as tall as his dad, but his face was boyish and he stood awkwardly. His younger sister, in jeans and a pink headscarf, studied me with interest. I smiled at them.

“And this is Hani, the interpreter,” I said. Hani, a young Somali woman, stepped forward and spoke in Arabic. She’d started at our clinic as a patient four years ago, but as her English was excellent and she couldn’t work as a dentist until she’d satisfied the Canadian professional requirements, she’d returned as an interpreter. We’d worked together for two years.

“Let’s start the visit with the whole family,” I proposed, “and then I can see you individually for specific issues as needed.” All four Haddads followed me to my exam room.

My assigned room was one of a dozen in the Raven Song Community Health Centre. It was in the rear of the building, positioned between the men’s washroom and the exit. This had always struck me as vaguely symbolic of the marginalization of my patients, and of the odd orbit of my medical career, on the fringe of regular family medicine.

I only saw newly arrived refugees. I was one of five physicians in British Columbia who did this work. We all practiced at Bridge Clinic, housed in the southeast corner of the Raven Song building. We all worked part-time because the work was difficult. I saw patients three days a week and stayed home with my kids the other four.

The

clinic saw approximately 1,800 new patients a year who came from around the world, mostly from United Nations refugee camps. It was a few blocks from Vancouver General Hospital, in the heart of the city. The specialists to whom I referred patients were stacked a dozen layers high in the medical office buildings just down Broadway. At noon I could strike out in any direction and find a satisfying lunch in minutes: congee, bagels, sushi, ramen. The neighbourhoods held heritage homes with porches and wildflower gardens set in a vibrant hub of traffic and sirens.

Exam room 146 was unassuming. It was smaller than the washroom across the hall and designed by someone who had never interacted with patients. A sink, cupboards, and a computer desk took up the far wall. The paper towel dispenser had been installed with an inch to spare above the counter, so that a paper jam had to be awkwardly dislodged after every crank of the handle. A plum-coloured vinyl exam table hugged the left wall, with two chairs wedged between the foot of the table and the sink. Whenever I did a Pap test, I had to reconfigure the room in order to extend the stirrups. The sharps container was mounted on the wall above the pair of chairs, precisely located so that seated adults struck their heads whenever they shifted position. Two more chairs were pushed against the opposite wall.

A red Tupperware box on the shelf held my preferred stationery, next to a Richard Scarry picture book for pediatric patients. At one point I had bought an aquarium, a self-sustaining ecosystem developed by NASA where shrimp, algae, and bacteria lived symbiotically in a sealed glass globe; I thought it would be a peaceful and harmonious point in the room. The shrimp kept dying, though, and this seemed an ominous message in a doctor’s office, so now my counter held only the usual tray of cotton swabs and rubber tourniquets. The respiratory therapist who used the room on my off days had hung educational posters on the walls. My colleague had grumbled at these when he poked his head in that morning: “Some of our patients have seen lungs, you know. Those pictures could trigger flashbacks.”

Yusef and Junah took the chairs beneath the sharps container, their daughter sat under the emphysema poster, and the son hauled himself onto the exam table. I took the chair at the computer desk, Hani next to me, and pulled up the family’s file.

The clinic nurses visit Welcome House to screen new arrivals shortly after their arrival in Canada, before their first appointment with a physician. I looked over their note. It began with the standard checklist:

Country of origin: Iraq

Country of transit: Egypt

Date of arrival in Canada: September 23

Occupation: Husband - journalist. Wife - engineer.

Children: Nadia (14), Layth (16) - developmental delay?

Trauma?

It went on to outline the medical history of each family member: surgeries, medication, chronic disease, allergies. My tasks today would be to determine whether further testing needed to be added to the routine screening blood work, renew any prescriptions, address any urgent issues, and outline a plan for future care.

Yusef and Junah deflected my questions about their medical histories. Their only concern was for their son, Layth.

“He can’t learn,” Hani interpreted. “Never went to school.”

Layth sat on the edge of the exam table, grinning, legs dangling. He was as sturdy as a man, charming as a boy. I observed him as his parents described his childhood: late to walk, late to talk, odd behaviour, such as hand flapping. He had no formal medical diagnosis. He had been inadmissible for school in their Iraqi hometown of Mosul. Junah had put her engineering career on hold to care for him. His widely spaced eyes, short neck, and monobrow made me wonder whether he had a genetic condition.

“Do any of your relatives have similar problems?” They didn’t.

“Were you related to each other before you were married?” Approximately 30 percent of marriages in Iraq are between first cousins. Consanguinity—literally “common blood”—was not unusual among my patients, especially those from Middle Eastern, West Asian, and North African cultures with a longstanding tradition of marriage between blood relatives.

“Their mothers are sisters,” confirmed Hani.

I arranged for Layth to return to see me for a full assessment. I expected he’d need referrals to Pediatrics and Medical Genetics.

“Their settlement worker told them he will go to school, but they don’t believe that is possible,” said Hani.

“Yes, he will go to school,” I confirmed. “In Canada, every child has a right to education. They’ll make accommodations for him—an aide, or special classes.”

After Hani relayed this, the parents turned to me with tears in their eyes. “Thank you, Doctor,” said Yusef, bowing his head and shoulders toward me.

“Thank you,” echoed Junah softly, also in English.

I knew I didn’t deserve any personal thanks. I was just lucky enough to be a frontline representative of the country that had offered them refuge; I was one of the first faces of hospitality newcomers met when they arrived.

I printed off the lab requisitions and tapped my notes into the computer. “Is this the whole family?” I asked, as the visit wound down. “Is anyone missing?” I’d learned not to assume that the family in front of me was intact. Older children sometimes remained in their home country to complete university. Sometimes an infant born after the family registered with the United Nations had to be left behind because the parents didn’t know they had to complete additional paperwork. Many patients had lived communally with extended family, but their elderly parents were too frail to travel or unwilling to leave their home.

Hani repeated my question in Arabic, and the entire family began to weep. It was a chorus: sobbing from Nadia, unrestrained bawling from Layth, low moaning from Junah, rapid speech from Yusuf as tears ran down his face. I sensed there was relief in the crying, as if they’d been waiting for an invitation to spill over.

During the exchange of Arabic, I waited. Crying no longer alarmed me. Some days every patient cried. The box of tissues on my counter got as much play as my stethoscope.

The story was this: Sami Haddad had been buried before his twelfth birthday.

Yusef had been a journalist in Mosul, in northern Iraq, for almost twenty years. He’d covered the culture and politics beats for Nineveh Radio. Yusef was not the first Iraqi journalist I’d seen at the refugee clinic. I knew that just being associated with an Iraqi newspaper or TV station that was seen by anti-government forces as supportive of the US-backed Iraqi government was risky. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 102 Iraqi journalists had been murdered over the past decade.1

A year and a half ago, as Yusef and his eleven-year-old son, Sami, played soccer in the courtyard of their home after dinner, a car pulled up. Masked gunmen dragged Yusef and Sami into the vehicle. They were held for three days, beaten, and dumped on the bank of the Tigris River. Sami died of a head injury. When Yusef had recovered from his injuries enough to travel, he fled to Egypt with his family. They registered with the United Nations Refugee Agency and arrived in Canada eighteen months later.

I knew that Yusef had heavily abbreviated the story, not for my benefit but to spare his wife and children. I didn’t press for details; I knew that eventually he would release them to me for safekeeping.

I’d listened to terrible stories, one after another, for years. The horror of this story, though, was magnified by Biblical themes: the Tigris River of the Garden of Eden; Nineveh of Jonah and the whale; violence on an Old Testament scale. It almost felt mythical. But the father in front of me opened his wallet, extracted a snapshot from the billfold compartment, and passed it to me

The boy in the picture was climbing a date palm: flip-flops, lean legs, long shorts, a yellow T-shirt. His head was silhouetted against the sky, hair a mess of black waves.

“That week he die,” Yusef said. “Last photo.”

As a physician, I kept my personal life strictly separate from work. I didn’t wear my wedding band, and there were no family portraits on my d

esk. I had children too, though—three of them at the time. My greatest fear was that I’d be unable to protect them from harm.

There was nothing I could say or do to make his son’s death right. “I’m so sorry,” I said. Ingrained professionalism kept my voice steady; they were only three words, but I looked at Yusef as I said them. I could see that they were enough.

That night, I ate dinner with my family at the beach near our home in Deep Cove, a thirty-minute commute from the clinic. After we’d cleared the picnic table, my husband, Pete, and I walked out to the dock and watched our kids playing along the shore. Our six-year-old son found a cluster of dandelions gone to seed; he hunched over, snapping the hollow milky stems and double fisting his prize.

“I’m going to make a wish!” said Leif. “I wish for . . .” I could see him searching for something extravagant. “A chocolate cake!” He puffed energetically, spit flying, and his lips almost touching the white fluff.

“Look, a school of wishes!” He watched them drift off in a hazy clump. “Hey! The wishes are all hugging each other!” And then he spotted some goslings and trotted off down the beach.

How wonderful to wish for chocolate cake, to have to think hard for something to wish for, to have all your needs met, to have no cares or sickness or worries to wish away. My children and their unspoiled interactions with the world were the most potent antidote to the suffering I witnessed at work and sometimes carried home with me like a bloodstain on my sleeve.

But once the kids were put to bed, and I settled on the couch to watch Netflix, I clicked past all the romantic comedies and TV sitcoms. I deliberated between Blood Diamond, Lost Boys of Sudan, and a Holocaust documentary. The awfulness overwhelmed me, but it felt disrespectful to enjoy something light after the day’s work, and I gravitated toward the heavy fare out of a sense of obligation. I knew it wasn’t good for me, but out of a perverse sense of solidarity with my patients, I immersed myself in scenes of injustice until bedtime.

2

I HAD A SECRET: I WASN’T working at the clinic because I had a heart for refugees.

Your Heart is the Size of Your Fist

Your Heart is the Size of Your Fist